Lymphatic system

| Lymphatic System | |

|---|---|

|

|

| An image displaying the lymphatic system. | |

| Latin | systema lymphoideum |

The lymphatic system in animals is a network of conduits that carry a clear fluid called lymph (from Latin lympha "water"[1]). It also includes the lymphoid tissue and lymphatic vessels through which the lymph travels in a one-way system in which lymph flows only toward the heart. Lymphoid tissue is found in many organs, particularly the lymph nodes, and in the lymphoid follicles associated with the digestive system such as the tonsils. The system also includes all the structures dedicated to the circulation and production of lymphocytes, which includes the spleen, thymus, bone marrow and the lymphoid tissue associated with the digestive system.[2] The lymphatic system as we know it today was first described independently by Olaus Rudbeck and Thomas Bartholin.

The blood does not directly come in contact with the parenchymal cells and tissues in the body, but constituents of the blood first exit the microvascular exchange blood vessels to become interstitial fluid, which comes into contact with the parenchymal cells of the body. Lymph is the fluid that is formed when interstitial fluid enters the initial lymphatic vessels of the lymphatic system. The lymph is then moved along the lymphatic vessel network by either intrinsic contractions of the lymphatic vessels or by extrinsic compression of the lymphatic vessels via external tissue forces (e.g. the contractions of skeletal muscles).

Contents |

Function

The lymphatic system has multiple interrelated functions:

- it is responsible for the removal of interstitial fluid from tissues

- it absorbs and transports fatty acids and fats as chyle to the circulatory system

- it transports immune cells to and from the lymph nodes in to the bone

- The lymph transports antigen-presenting cells (APCs), such as dendritic cells, to the lymph nodes where an immune response is stimulated.

- The lymph also carries lymphocytes from the efferent lymphatics exiting the lymph nodes.

Clinical significance

The study of lymphatic drainage of various organs is important in diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of cancer. The lymphatic system, because of its physical proximity to many tissues of the body, is responsible for carrying cancerous cells between the various parts of the body in a process called metastasis. The intervening lymph nodes can trap the cancer cells. If they are not successful in destroying the cancer cells the nodes may become sites of secondary tumors.

Diseases and other problems of the lymphatic system can cause swelling and other symptoms. Problems with the system can impair the body's ability to fight infections.

Organization

The lymphatic system can be broadly divided into the conducting system and the lymphoid tissue.

- The conducting system carries the lymph and consists of tubular vessels that include the lymph capillaries, the lymph vessels, and the right and left thoracic ducts.

- The lymphoid tissue is primarily involved in immune responses and consists of lymphocytes and other white blood cells enmeshed in connective tissue through which the lymph passes. Regions of the lymphoid tissue that are densely packed with lymphocytes are known as lymphoid follicles. Lymphoid tissue can either be structurally well organized as lymph nodes or may consist of loosely organized lymphoid follicles known as the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT)

Lymphoid tissue

Lymphoid tissue associated with the lymphatic system is concerned with immune functions in defending the body against the infections and spread of tumors. It consists of connective tissue with various types of white blood cells enmeshed in it, most numerous being the lymphocytes.

The lymphoid tissue may be primary, secondary, or tertiary depending upon the stage of lymphocyte development and maturation it is involved in. (The tertiary lymphoid tissue typically contains far fewer lymphocytes, and assumes an immune role only when challenged with antigens that result in inflammation. It achieves this by importing the lymphocytes from blood and lymph.[3])

Primary lymphoid organs

The central or primary lymphoid organs generate lymphocytes from immature progenitor cells.

The thymus and the bone marrow constitute the primary lymphoid tissues involved in the production and early selection of lymphocytes.

Secondary lymphoid organs

Secondary or peripheral lymphoid organs maintain mature naive lymphocytes and initiate an adaptive immune response. The peripheral lymphoid organs are the sites of lymphocyte activation by antigen. Activation leads to clonal expansion and affinity maturation. Mature Lymphocytes recirculate between the blood and the peripheral lymphoid organs until they encounter their specific antigen.

Secondary lymphoid tissue provides the environment for the foreign or altered native molecules (antigens) to interact with the lymphocytes. It is exemplified by the lymph nodes, and the lymphoid follicles in tonsils, Peyer's patches, spleen, adenoids, skin, etc. that are associated with the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT).

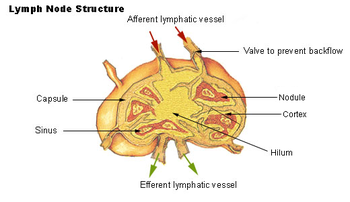

Lymph nodes

A lymph node is an organized collection of lymphoid tissue, through which the lymph passes on its way to returning to the blood. Lymph nodes are located at intervals along the lymphatic system. Several afferent lymph vessels bring in lymph, which percolates through the substance of the lymph node, and is drained out by an efferent lymph vessel.

The substance of a lymph node consists of lymphoid follicles in the outer portion called the "cortex", which contains the lymphoid follicles, and an inner portion called "medulla", which is surrounded by the cortex on all sides except for a portion known as the "hilum". The hilum presents as a depression on the surface of the lymph node, which makes the otherwise spherical or ovoid lymph node bean-shaped. The efferent lymph vessel directly emerges from the lymph node here. The arteries and veins supplying the lymph node with blood enter and exit through the hilum.

Lymph follicles are a dense collection of lymphocytes, the number, size and configuration of which change in accordance with the functional state of the lymph node. For example, the follicles expand significantly upon encountering a foreign antigen. The selection of B cells occurs in the germinal center of the lymph nodes.

Lymph nodes are particularly numerous in the mediastinum in the chest, neck, pelvis, axilla (armpit), inguinal (groin) region, and in association with the blood vessels of the intestines.[2]

Lymphatics

Tubular vessels transport back lymph to the blood ultimately replacing the volume lost from the blood during the formation of the interstitial fluid. These channels are the lymphatic channels or simply called lymphatics.[4]

Function of the fatty acid transport system

Lymph vessels called lacteals are present in the lining of the gastrointestinal tract, predominantly in the small intestine. While most other nutrients absorbed by the small intestine are passed on to the portal venous system to drain via the portal vein into the liver for processing, fats (lipids) are passed on to the lymphatic system to be transported to the blood circulation via the thoracic duct. (There are exceptions, for example Medium chain triglycerides (MCTs) are fatty acid esters of glycerol that passively diffuse from the GI tract to the portal system.) The enriched lymph originating in the lymphatics of the small intestine is called chyle. As the blood circulates, fluid leaks out into the body tissues. This fluid is important because it carries food to the cells and waste back to the bloodstream. The nutrients that are released to the circulatory system are processed by the liver, having passed through the systemic circulation. The lymph system is a one-way system, transporting interstitial fluid back to blood.

Diseases of the lymphatic system

Lymphedema is the swelling caused by the accumulation of lymph fluid,[5] which may occur if the lymphatic system is damaged or has malformations. It usually affects the limbs, though face, neck and abdomen may also be affected.

Some common causes of swollen lymph nodes include infections, infectious mononucleosis, and cancer, e.g. Hodgkin's and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, and metastasis of cancerous cells via the lymphatic system. In elephantiasis, infection of the lymphatic vessels cause a thickening of the skin and enlargement of underlying tissues, especially in the legs and genitals. It is most commonly caused by a parasitic disease known as lymphatic filariasis. Lymphangiosarcoma is a malignant soft tissue tumor (soft tissue sarcoma), whereas lymphangioma is a benign tumor occurring frequently in association with Turner syndrome. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis is a benign tumor of the smooth muscles of the lymphatics that occurs in the lungs.

Development of lymphatic tissue

Lymphatic tissues begin to develop by the end of the fifth week of embryonic development. Lymphatic vessels develop from lymph sacs that arise from developing veins, which are derived from mesoderm.

The first lymph sacs to appear are the paired jugular lymph sacs at the junction of the internal jugular and subclavian veins. From the jugular lymph sacs, lymphatic capillary plexuses spread to the thorax, upper limbs, neck and head. Some of the plexuses enlarge and form lymphatic vessels in their respective regions. Each jugular lymph sac retains at least one connection with its jugular vein, the left one developing into the superior portion of the thoracic duct.

The next lymph sac to appear is the unpaired retroperitoneal lymph sac at the root of the mesentery of the intestine. It develops from the primitive vena cava and mesonephric veins. Capillary plexuses and lymphatic vessels spread from the retroperitoneal lymph sac to the abdominal viscera and diaphragm. The sac establishes connections with the cisterna chyli but loses its connections with neighboring veins.

The last of the lymph sacs, the paired posterior lymph sacs, develop from the iliac veins. The posterior lymph sacs produce capillary plexuses and lymphatic vessels of the abdominal wall, pelvic region, and lower limbs. The posterior lymph sacs join the cisterna chyli and lose their connections with adjacent veins.

With the exception of the anterior part of the sac from which the cisterna chyli develops, all lymph sacs become invaded by mesenchymal cells and are converted into groups of lymph nodes.

The spleen develops from mesenchymal cells between layers of the dorsal mesentery of the stomach. The thymus arises as an outgrowth of the third pharyngeal pouch.

History

Hippocrates was one of the first persons to mention the lymphatic system in fifth century BC. In his work "On Joints," he briefly mentioned the lymph nodes in one sentence. Rufus of Ephesus, a Roman physician, identified the axillary, inguinal and mesenteric lymph nodes as well as the thymus during the first to second century AD.[6] The first mention of lymphatic vessels was in 3rd century BC by Herophilus, a Greek anatomist living in Alexandria, who incorrectly concluded that the "absorptive veins of the lymphatics", by which he meant the lacteals (lymph vessels of the intestines), drained into the hepatic portal veins, and thus into the liver.[6] Findings of Ruphus and Herophilus findings were further propagated by the Greek physician Galen, who described the lacteals and mesenteric lymph nodes which he observed in his dissection of apes and pigs in the second century A.D.[6][7]

Until the seventeenth century, ideas of Galen were most prevalent. Accordingly, it was believed that the blood was produced by the liver from chyle contaminated with ailments by the intestine and stomach, to which various spirits were added by other organs, and that this blood was consumed by all the organs of the body. This theory required that the blood be consumed and produced many times over. His ideas had remained unchallenged until the seventeenth century, and even then were defended by some physicians.[7]

.jpg)

In the mid 16th century Gabriel Fallopius (discoverer of the Fallopian Tubes) described what are now known as the lacteals as "coursing over the intestines full of yellow matter."[6] In about 1563 Bartolomeo Eustachi, a professor of anatomy, described the thoracic duct in horses as vena alba thoracis.[6] The next breakthrough came when in 1622 a physician, Gasparo Aselli, identified lymphatic vessels of the intestines in dogs and termed them venae alba et lacteae, which is now known as simply the lacteals. The lacteals were termed the fourth kind of vessels (the other three being the artery, vein and nerve, which was then believed to be a type of vessel), and disproved Galen's assertion that chyle was carried by the veins. But, he still believed that the lacteals carried the chyle to the liver (as taught by Galen).[8] He also identified the thoracic duct but failed to notice its connection with the lacteals.[6] This connection was established by Jean Pecquet in 1651, who found a white fluid mixing with blood in a dog's heart. He suspected that fluid to be chyle as its flow increased when abdominal pressure was applied. He traced this fluid to the thoracic duct, which he then followed to a chyle-filled sac he called the chyli receptaculum, which is now known as the cisternae chyli; further investigations led him to find that lacteals' contents enter the venous system via the thoracic duct.[6][8] Thus, it was proven convincingly that the lacteals did not terminate in the liver, thus disproving Galen's second idea: that the chyle flowed to the liver.[8] Johann Veslingius drew the earliest sketches of the lacteals in humans in 1647.[7]

The idea that blood recirculates through the body rather than being produced anew by the liver and the heart was first accepted as a result of works of William Harvey—a work he published in 1628. In 1652, Olaus Rudbeck (1630–1702), a Swede, discovered certain transparent vessels in the liver that contained clear fluid (and not white), and thus named them hepatico-aqueous vessels. He also learned that they emptied into the thoracic duct, and that they had valves.[8] He announced his findings in the court of Queen Christina of Sweden, but did not publish his findings for a year,[9] and in the interim similar findings were published by Thomas Bartholin, who additionally published that such vessels are present everywhere in the body, and not just the liver. He is also the one to have named them "lymphatic vessels".[8] This had resulted in a bitter dispute between one of Bartholin's pupils, Martin Bogdan,[10] and Rudbeck, whom he accused of plagiarism.[9]

See also

- Lymphangiogenesis

- Lymphedema

- Lymphoma

- American Society of Lymphology

- Manual lymphatic drainage

- Reticuloendothelial system

References

- ↑ "Lymph - Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary". www.merriam-webster.com. http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/lymph. Retrieved 2010-05-29.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Warwick, Roger; Peter L. Williams. "Angiology (Chapter 6)". Gray's anatomy. illustrated by Richard E. M. Moore (Thirty-fifth ed.). London: Longman. pp. 588–785.

- ↑ Goldsby, Richard; Kindt, TJ; Osborne, BA; Janis Kuby (2003) [1992]. "Cells and Organs of the Immune System (Chapter 2)". Immunology (Fifth ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. pp. 24–56. ISBN 07167-4947-5.

- ↑ "Definition of lymphatics". Webster's New World Medical Dictionary. MedicineNet.com. http://www.medterms.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=4217. Retrieved 2008-07-06.

- ↑ "Lymphedema". http://www.merck.com/mmhe/sec03/ch037/ch037b.html.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Ambrose, C. (2006). "Immunology’s first priority dispute—An account of the 17th-century Rudbeck–Bartholin feud". Cellular Immunology 242 (1): 1. doi:10.1016/j.cellimm.2006.09.004. PMID 17083923.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Fanous, Medhat YZ; Anthony J Phillips, John A Windsor (2007). "Mesenteric Lymph: The Bridge to Future Management of Critical Illness". Journal of the Pancreas (Department of Internal Medicine and Gastroenterology ALMA MATER STUDIORUM - UNIVERSITY OF BOLOGNA) 8 (4): 374–399. PMID 17625290. http://www.joplink.net/prev/200707/06.html. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Flourens, P. (1859). "ASELLI, PECQUET, RUDBECK, BARTHOLIN (Chapter 3)". A History of the Discovery of the Circulation of the Blood. Rickey, Mallory & company. pp. 67–99. http://books.google.com/?id=4QqS6LrYWf4C&printsec=frontcover&dq=william+harvey. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Eriksson, G. (2004). "Olaus Rudbeck as scientist and professor of medicine (Original article in Swedish)" (in Swedish). Svensk Medicinhistorisk Tidskrift 8 (1): 39–44. PMID 16025602.

- ↑ "Disputatio anatomica, de circulatione sanguinis". Account of Rudbeck's work on lymphatic system and dispute with Bartholin. The International League of Antiquarian Booksellers. http://www.ilab.org/db/detail.php?booknr=349906004. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

External links

- Lymphatic System

- Lymphatic System Overview (innerbody.com)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||